China’s Health Care and Foreign Investment†

Table of Contents

Estimated Reading Time

- 5 min

The World Health Organization (“WHO”) has projected that, compared with 2018, nearly 360 million more people in China will enjoy improvements in health and wellbeing in 2025. To meet this target, among others, and to prepare for health care challenges arising from significant demographic changes occurring in China, the Chinese leadership has introduced various measures, including allowing the establishment of wholly foreign-owned hospitals in nine localities.

These measures and related plans to improve China’s medical insurance system should be welcomed by foreign investors. However, a major problem lies in whether China is ready to amend legal rules to reduce the legal risks associated with medical practice as potential criminal consequences are likely to deter foreign medical professionals, especially those with expert knowledge and skills, from practicing in China.

China’s Health Care Targets and Demographic Changes

Apart from the target mentioned above, the WHO has also stated that, compared with 2018, China is expected to see approximately 78 million more people who are “covered by essential services” while “not experiencing financial hardship” in 2025, along with nearly 30 million more people who are “protected from health emergencies”.

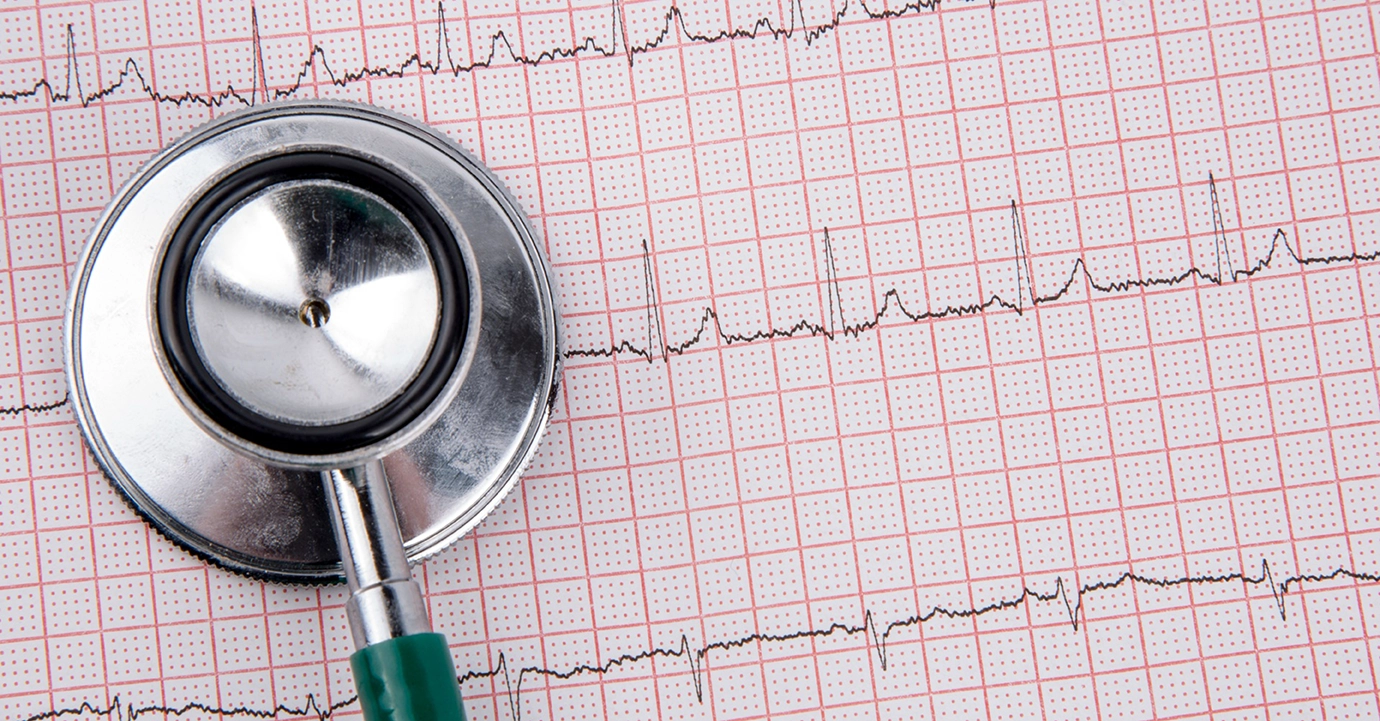

It is unclear whether China will be able to meet these WHO targets by the end of 2025. Regardless, the country’s efforts to meet the targets will prepare it well for coping with a bigger challenge: demographic changes. China’s population is currently both decreasing and aging (see Image One). Data provided by the WHO show that the population in the country is expected to decrease from 1.42 billion in 2023 to 1.26 billion in 2050. The number of people who are 60 years old or older is expected to increase from 278.3 million (i.e., nearly 20 percent of the total population) in 2023 to 503.9 million in 2050 (i.e., nearly 40 percent of the total population).

“[…] there is an urgent need to increase the capacity and capabilities of China’s health care system.”

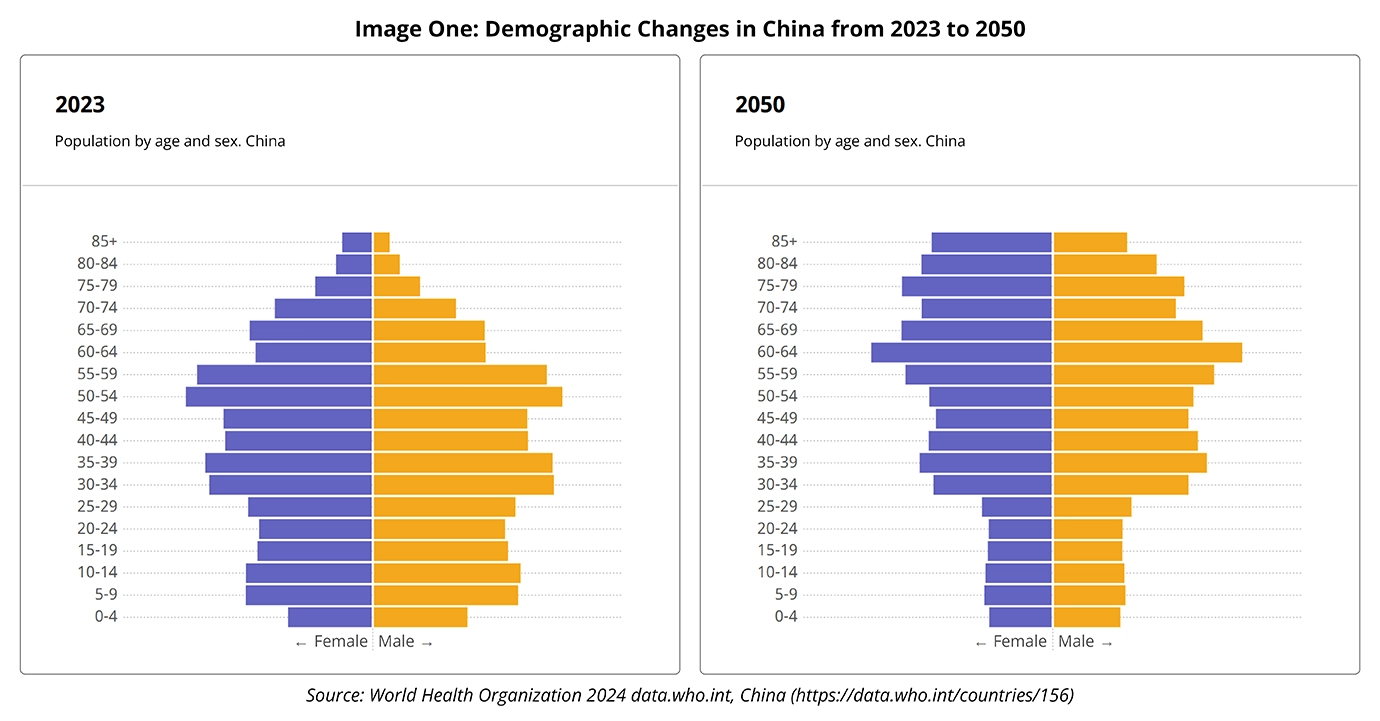

The doubling of the number of elders in less than two decades puts pressure on the health care system in China, where the density of doctors and density of nurses are far below the figures seen in developed countries, such as Australia, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States (see Image Two). As the top causes of death in China include stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and other forms of dementia—diseases that often demand intensive and long-term care—there is an urgent need to increase the capacity and capabilities of China’s health care system.

Wholly Foreign-Owned Hospitals

To address the need for a better health care system in the country, Chinese authorities recently issued a new measure to allow wholly foreign-owned hospitals to be established in Hainan Province, three provincial-level cities (i.e., Beijing, Shanghai, and Tianjin), and five large cities (i.e., Fuzhou, Guangzhou, Nanjing, Shenzhen, and Suzhou). All of these locations, where many foreigners reside, play important roles in the country’s efforts to attract foreign investment.

Foreign investors seeking to gain approvals to establish wholly foreign-owned hospitals in these localities are required to provide “internationally advanced hospital management concepts, management models, and service models” and “internationally leading medical technologies and equipment”, as well as meet other conditions.

“A group from Singapore quickly seized the opportunity to gain approvals to establish a wholly foreign-owned hospital in Guangzhou.”

A group from Singapore quickly seized the opportunity to gain approvals to establish a wholly foreign-owned hospital in Guangzhou. The 500-bed hospital is scheduled to begin offering medical services in 2026. According to public announcements, the hospital will focus on strengthening cooperation and exchange mechanisms between China’s top hospitals and those in Singapore, Europe, and the United States. In addition, the hospital will introduce to China cutting-edge technologies such as Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, which is a cancer treatment that uses a patient’s genetically modified T cells to find and destroy cancer cells.

Legal Risks

These wholly foreign-owned hospitals are permitted to recruit foreign doctors, doctors from Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan, and other health professionals from Hong Kong and Macao for short-term practice, so long as the proportion of health professionals and management staff from mainland China are not less than 50% of the total number of such personnel.

To attract excellent foreign medical professionals, these hospitals will likely offer generous recruitment packages. However, these professionals should be concerned about potential criminal consequences associated with medical practice in China. According to a provision of China’s Criminal Law, any medical personnel who, due to “serious irresponsibility”, causes the death of a patient or “severely harms the health of a patient” can be subject to imprisonment of up to three years.

In 2008, China’s Ministry of Public Security and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, both of which oversee the investigation and prosecution of crimes committed in the country, issued rules (still effective) to explain the meanings of the terms used in the above-mentioned criminal provision. The term “serious irresponsibility” is defined to cover six different situations, including “leaving the post without permission”, followed by a catch-all phrase: “other situations [showing] serious irresponsibility”. The term “severely harms the health of a patient” is defined as “causing the patient to be severely disabled, severely injured, or infected with difficult-to-cure disease(s) such as AIDS and viral hepatitis”, followed by a catch-all phrase: “other consequences that severely harm the health of a patient”.

The legal risks arising from these unclear definitions are so enormous that foreign medical professionals are likely to be deterred from practicing in China. If the Chinese leadership is committed to leveraging the knowledge and skills of top medical professionals from around the world to improve the country’s health care system, the criminal provision and related rules discussed above should be amended without delay.

- The citation of this article is: The Editorial Board of SINOTALKS®, China’s Health Care and Foreign Investment, SINOTALKS.COM®, SinoExpress™, Jan. 15, 2025, https://sinotalks.com/sinoexpress/health-care-foreign-investment. ↩︎