The China–Laos Railway:

Potential Opportunities Amid Global Crises†

Table of Contents

- The China–Laos Railway Shows Progress

- Legal Safeguards Required to Make Opportunities Promising

- China’s Guiding Case No. 109 & International Rules on Independent Demand Guarantees

- Key Takeaway

Estimated Reading Time

- 7 min

The Ukraine crisis is a major blow to a world that has already been hit hard by the pandemic and economic setbacks. Businesses struggling to stay afloat should ask: where are the much-needed opportunities amid the current global crises? The China–Laos Railway may be a source of such opportunities, which, as explained below, could become promising if supported by proper legal safeguards.

The China–Laos Railway Shows Progress

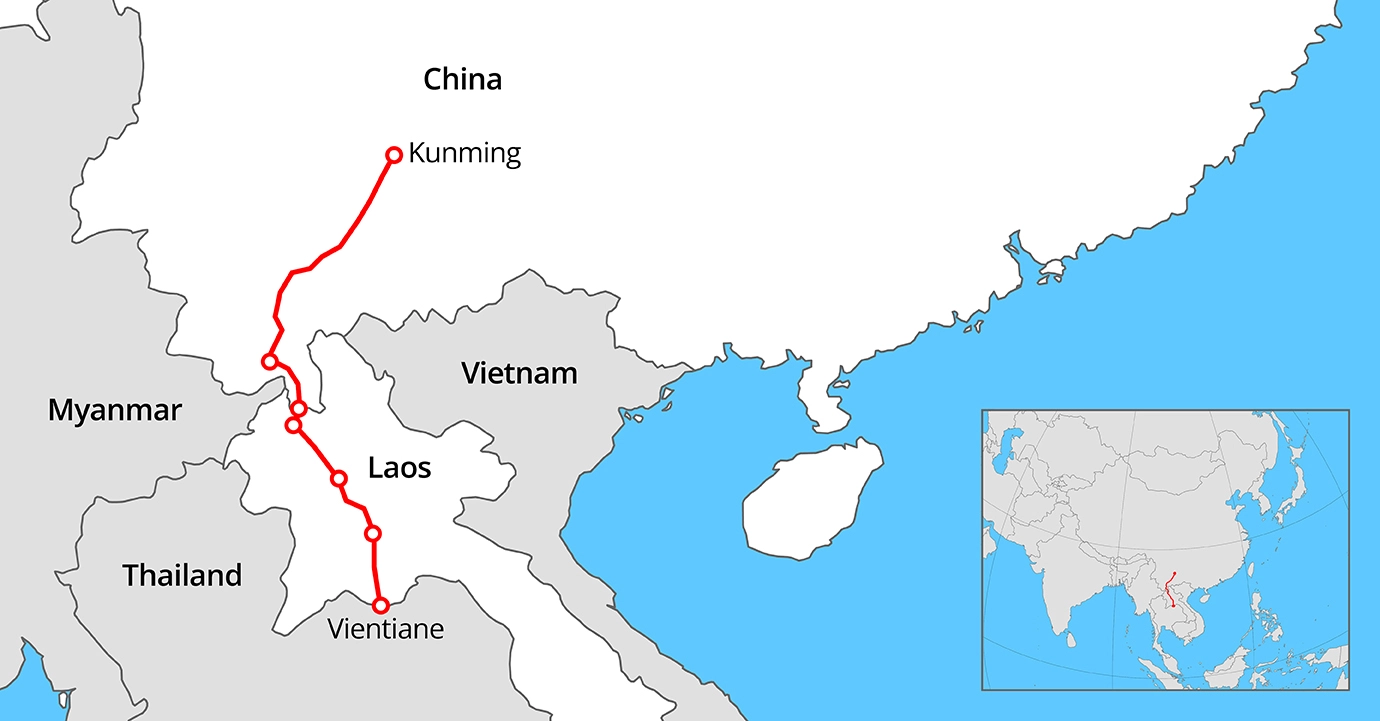

Beginning operations on December 3, 2021, the 1000 km-long China–Laos Railway connects Kunming, the capital city of China’s southwestern province Yunnan, with Vientiane, the capital and largest city of Laos. Running through mountains and valleys, the high-speed trains have shortened the travel time between Kunming and Vientiane to only about 10 hours, giving landlocked Laos an unprecedented prospect to become a hub of economic activities.

According to official reports, the China–Laos Railway has, despite the pandemic, been running smoothly since its operation began. So far, a total of nearly 200,000 tons of goods and 1 million passengers have been carried by the trains. With their significant stakes in this USD 6 billion railway project, both China and Laos are likely to take various business-friendly steps to maximize the return on their investments.

Legal Safeguards Required to Make Opportunities Promising

The progress of the China–Laos Railway is impressive. Businesses attempting to seize opportunities arising from this railway must, however, also wonder: what legal safeguards are available to make these opportunities promising?

Take construction projects as an example. The potential influx of travelers and businesses to Laos will likely boost the need for residential and commercial buildings in this largely agricultural country. Given the logistical convenience offered by the China–Laos Railway, Chinese contractors and builders can easily send building materials and experienced construction teams to Laos, thereby giving them an advantage to win construction projects in Laos. This advantage, while attractive, could pale into insignificance if the Chinese contractors and builders cannot provide sufficient legal safeguards to protect the interests of the developers. It is this context that reflects the importance of the principles established in China’s Guiding Case No. 109, to which I now turn.

China’s Guiding Case No. 109 & International Rules on Independent Demand Guarantees

Guiding Case No. 109 (Anhui Foreign Economic Construction (Group) Co., Ltd. v. Inmobiliaria Palacio Oriental, S.A., A Dispute over Guarantee Fraud) is a good example to show how bank guarantees can support a construction project involving a Chinese contractor and its builder on the one side and a foreign developer on the other.

Specifically, Guiding Case No. 109 concerns a construction project in Costa Rica developed by a company in that country with support from a Chinese contractor and its builder. Legal safeguards in the form of two bank guarantees were set up to ensure the quality of the construction:

- an independent demand guarantee issued by a bank in Costa Rica to the beneficiary of the guarantee, i.e., the developer. To execute this guarantee, the developer had to submit various documents to the bank in Costa Rica, specifying the grounds for the execution of the guarantee (e.g., Chinese contractor/builder’s breach of the construction contract).

- a related independent demand counter-guarantee issued by a bank in China to the bank in Costa Rica. The essence of this counter-guarantee was to indicate the bank in China’s undertaking to pay the bank in Costa Rica the same amount that the latter would pay to the developer should the demand guarantee be executed. Described as “unconditional, irrevocable, and required to be paid at any time”, this counter-guarantee clearly stated that the Uniform Rules for Demand Guarantees of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC Product No. 458E, 1992 Edition) had to be followed.

During the performance of the construction contract, the developer in Costa Rica discovered “inferior quality” in the construction and refused to pay a certain amount specified in the construction contract. Because of the “inferior quality”, the developer also filed a claim with the bank in Costa Rica for the payment of USD 2,008,000 under the demand guarantee on the grounds that the Chinese contractor and builder breached the contract. Following the terms of the guarantee, the bank in Costa Rica paid the developer accordingly in March 2012. Afterwards, the bank in Costa Rica demanded that the bank in China pay it the same amount (i.e., USD 2,008,000) under the counter-guarantee.

At issue was whether the bank in China had to pay this amount. The answer would have been a straightforward “yes” had the following developments not occurred:

- The day before the developer’s filing a claim under the demand guarantee, the Chinese builder applied for arbitration against the developer, arguing that the developer was in arrears on the construction cost and corresponding interest due for completed parts of construction.

- Approximately a year and a half later, i.e., in July 2013, an arbitral award was issued against the developer, which, due to the arrears, was determined to have seriously breached the construction contract (note: the developer challenged the award in the Supreme Court of the Republic of Costa Rica but lost the suit.)

In light of these developments, the Chinese contractor argued that the developer’s claim for payment under the demand guarantee constituted fraud and, therefore, the bank in China had no obligation to pay under the counter-guarantee. Based on detailed analyses of related legal rules and principles, including the Uniform Rules for Demand Guarantees of the International Chamber of Commerce, the Supreme People’s Court of China decided that:

- the bank in Costa Rica had rightly followed the terms of its guarantee to pay the agreed amount (i.e., USD 2,008,000) to the developer; and

- the bank in China, therefore, had to pay the same amount under the counter-guarantee to the bank in Costa Rica.

Please read the full text of Guiding Case No. 109 here to understand how the Supreme People’s Court articulated its reasoning, the key points of which have been summarized as the Guiding Case’s “Main Points of the Adjudication” to guide Chinese courts handling similar cases in the future (for an explanation of the nature of Guiding Cases, see SINOTALKS.COM In Brief No. 2). One of the “Main Points of the Adjudication” is as follows:

When the underlying transaction of an independent guarantee needs to be reviewed [by a people’s court] to determine [whether the beneficiary’s claim for payment] constituted fraud, the principles of limitedness and necessity should be adhered to. The scope of the review should be limited to [reviewing] whether the beneficiary knew that the counterparty of the underlying contract [(which, in Guiding Case No. 109, means the construction contract)] did not do anything amounting to a breach of the underlying contract, and whether the beneficiary knew that there were no facts [enabling] the beneficiary [to exercise] the right to request payment [under the guarantee]. (emphasis added)

The rationale behind the above approach is, as put by the Supreme People’s Court: “Otherwise, the review of the underlying contract will destabilize the value of the ‘payment on demand’ system of independent guarantees.”

In the judgment, the Supreme People’s Court made this point clear: the developer’s breach of the construction contract did not necessarily make its request for payment under the independent guarantee fraudulent. As a result, the Supreme People’s Court ruled against the Chinese contractor because it did not adduce sufficient evidence to prove that the developer requested payment under the independent guarantee with the knowledge that it had no grounds to do so.

Key Takeaway

Guiding Case No. 109 specifically shows the Supreme People’s Court’s firm adherence to legal rules and principles that protect the value of the “payment on demand” system of independent guarantees. This is a welcome development. Businesses seeking to develop construction projects in Laos should learn from this case that carefully crafted terms of independent guarantees can give them important legal safeguards. To understand what the terms of the independent guarantee in Guiding Case No. 109 were, please read SINOTALKS.COM’s bilingual version of the case.

† The citation of this article is: Dr. Mei Gechlik, The China–Laos Railway: Potential Opportunities Amid Global Crises, SINOTALKS.COM, In Brief No. 7, Mar. 9, 2022, https://sinotalks.com/inbrief/2022w09-english. This article was first published on LinkedIn on March 2, 2022, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/chinalaos-railway-potential-opportunities-amid-global-dr-mei-gechlik.

The original, English version of this article was edited by Nathan Harpainter. The information and views set out in this article are the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the work or views of SINOTALKS.COM.