Determining Damages in Trade Secret Cases:

China’s Landmark Case vs. U.S. Experiences†

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- China’s Landmark Trade Secret Case

- China’s Innovative Approach to Determining Damages

- U.S. Experiences

- Concluding Remarks

Estimated Reading Time

- 15 min

(Publicomainpictures.net)

Introduction

An important benchmark to determine the strength of judicial protection of intellectual property (“IP”) rights is the extent to which victims of IP infringement can obtain meaningful damages in a court of law. The amounts of such damages reflect the judiciary’s commitment to not only compensate victims of IP infringement but also punish the infringers and deter others from committing similar acts.

Judicial protection of IP rights in China has been perceived to be limited largely because the amounts of damages awarded by Chinese courts in IP infringement cases have historically been small, especially in comparison to those awarded by U.S. courts in similar cases. However, this state of affairs may be changing, as China’s Supreme People’s Court (“SPC”) rendered a landmark judgment in a case involving large-scale infringement of trade secrets, allowing the victims to receive an amount equivalent to almost USD 90 million as compensation—the highest amount ever awarded by a Chinese court in an IP infringement lawsuit.

In the landmark case, the SPC overcame challenges presented by complicated circumstances involved to innovatively calculate the amount of “benefits” obtained by the defendant company from its infringement of the plaintiff company’s trade secrets. The significance of the case was recognized in September 2024, when it was selected as a Typical Case to provide guidance to Chinese courts handling similar cases.1 The case was further commended in early 2025, when the People’s Courts Daily featured an article discussing actions taken by the Chinese judiciary to strengthen “new quality productive forces”, a concept emphasized by President XI Jinping to drive the high-tech development in China.2

As analyzed below, the innovative approach taken by the SPC to calculate the damages in the landmark case is essentially based on the concept of “unjust enrichment”. The steps followed by the SPC to do the calculation are helpful but inadequate. To help China develop its jurisprudence in this important area, this article discusses related U.S. experiences. After years of facing various challenges in determining when the “unjust enrichment” approach should be applied in trade secret cases and how “unjust enrichment” should be calculated, the U.S. judiciary has developed a comprehensive body of principles that can be a useful reference for Chinese courts.

China’s Landmark Trade Secret Case

On April 25, 2024, the SPC rendered a final judgment in a lawsuit brought by Zhejiang Geely Holding Group and its associated companies (collectively referred to as “Geely”) against WM Motor Technology Group Co., Ltd. and its associated companies (collectively referred to as “WM Motor”) for infringing Geely’s trade secrets. Issued a day before the World Intellectual Property Day, the judgment has since then attracted widespread attention as the unprecedentedly large award to the plaintiff seems to signal a new path for the development of IP in China.

“[…] Geely noticed that almost forty of its former product management and technical personnel had joined WM Motor within a short time after they left Geely.”

The case originated in 2018, when Geely noticed that almost forty of its former product management and technical personnel had joined WM Motor within a short time after they left Geely. With assistance from these individuals, WM Motor was able to incorporate Geely’s proprietary technology into WM Motor’s electric vehicles and apply for related patents that were later found to lack novelty.

At the trial court level, the High People’s Court of Shanghai Municipality (“Shanghai High Court”) ruled that WM Motor had infringed Geely’s trade secrets by strategically recruiting Geely’s former employees and engaging them in illegally using Geely’s proprietary technology. The court ordered WM Motor to pay, inter alia, RMB 5 million as compensation for Geely’s economic losses.3

On appeal, the SPC corrected the mistake made by the Shanghai High Court, which had determined the extent of infringement to be of narrower scope, and increased the amount of compensation for Geely’s economic losses by approximately 128 times to nearly RMB 640 million.4 Almost two-thirds of the damages awarded are punitive in nature to punish WM Motor for infringing trade secrets on an incredibly large scale and to deter others from committing similar acts. In fact, when this case was selected as a Typical Case, its significance was described as follows:

This is a typical case [showing] effective crack down on organized, planned, and large-scale infringements of technological secrets. [… The court] has fully demonstrated its clear attitude toward strict protection of intellectual property rights and its firm determination to combat unfair competition. [Such attitude and determination] are conducive to creating a rule-of-law environment that respects originality and fair competition and that protects scientific and technological innovations.

[emphasis added]

China’s Innovative Approach to Determining Damages

To calculate the damages for covering Geely’s economic losses, the SPC adopted, in accordance with the Anti-Unfair Competition Law of the People’s Republic of China applicable at the time (“Anti-Unfair Competition Law 2019”).5 an approach that is essentially based on the concept of unjust enrichment. Specifically, the Anti-Unfair Competition Law 2019 allowed a court to base the calculation of damages on the “benefits” the defendant obtained as a result of his infringement in situations where it is difficult to base the calculation on the “losses” the plaintiff suffered.6

In many cases, courts can calculate the “benefits” obtained by the defendant by considering either the additional profits the defendant received that were attributable to the infringement of the plaintiff’s IP, or the R&D costs saved by the defendant as a result of the infringement. In the Geely versus WM Motor case, however, the SPC could not apply either consideration because WM Motor did not make profits during the period at issue and there was no direct evidence regarding the R&D costs saved by WM Motor.

“[…] the SPC arrived at the calculation of the benefits obtained by WM Motor from its infringement of Geely’s technological secrets by following three steps […].”

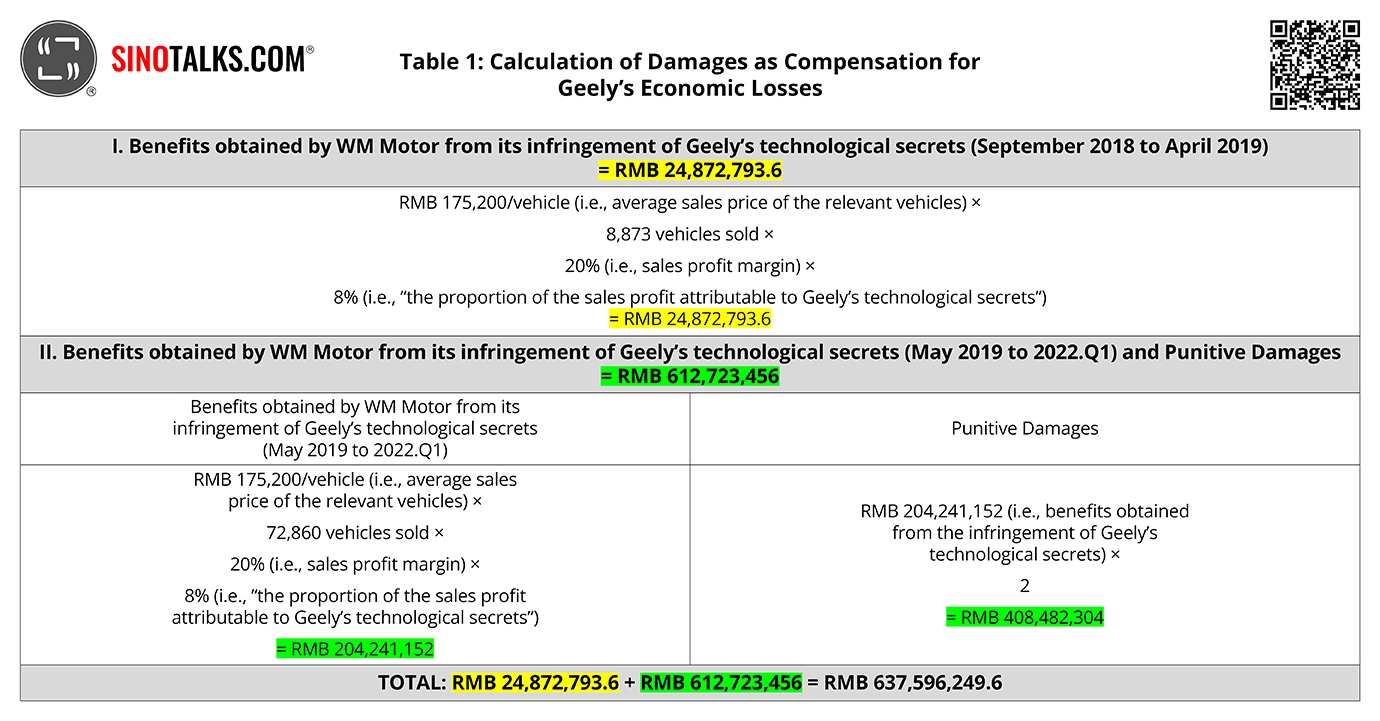

Despite these challenges, the SPC arrived at the calculation of the benefits obtained by WM Motor from its infringement of Geely’s technological secrets by following three steps as explained below and summarized in Table 1.

- Step One: Identifying WM Motor’s vehicles that were developed by utilizing Geely’s technological secrets (“relevant vehicles”).

The SPC identified WM Motor’s EX series electric vehicles (including the EX5, EX6, and E5 models) as vehicles developed by utilizing Geely’s technological secrets at issue. The court reached this conclusion because it only took WM Motor, which was established in May 2016, slightly more than two years to bring its EX5 vehicles to the market in September 2018. As WM Motor did not have related technological experiences or legal access to the technology used in these vehicles, the mass and rapid production of these vehicles was a result of utilizing Geely’s technological secrets. According to the SPC, the infringement not only saved WM Motor’s R&D costs but also “shortened the product launch time, enhancing [the company’s] competitive advantage on the market”.

- Step Two: Calculating the proportion of WM Motor’s profits from sales of the relevant vehicles that were attributable to its infringement of Geely’s trade secrets.

The calculation was based on the multiplication of four factors: (1) the average sales price of the relevant vehicles, (2) the total number of these vehicles sold during the periods at issue, (3) the profit margin of those sales, and (4) “the proportion of the sales profit attributable to Geely’s technological secrets”.

Regarding the first two factors, the SPC drew on related figures stated in the listing prospectus submitted by WM Motor to the Hong Kong Stock Exchange Limited (“Prospectus”)—an important piece of evidence that was the subject of intensive cross-examination by both Geely and WM Motor.

To determine the third factor, i.e., the sales profit margin, the SPC did not agree with Geely’s argument that this factor should be based on the average gross profit margin of 54.6% included in the Prospectus, stating that it was inappropriate to use this number when WM Motor was “actually in a loss-making state”. Instead, without clear explanations, the SPC referred to the gross profit margins of electric cars produced by “representative enterprises” in this industry during the same period (i.e., 10.6%-17.9%). Based on these margins, the SPC quite arbitrarily adopted “20%” as the sales profit margin in this case. It remains unclear to what extent the gross profit margins of “representative enterprises” in the same industry should be relied upon to infer the sales profit margin of a defendant enterprise.

As for the fourth factor, i.e., “the proportion of the sales profit attributable to Geely’s technological secrets”, the SPC only briefly stated that a figure of “8%”—which was significantly lower than Geely’s requested measure of 32%—should be chosen. According to the judgment, this percentage was based on the court’s “comprehensive consideration” of various elements, including the nature of WM Motor’s infringement. Neither the list of all considered elements nor the method used by the SPC to weigh them is known.

- Step Three: Calculating punitive damages.

Unlike older versions, the Anti-Unfair Competition Law 2019 allowed Chinese courts to award punitive damages if the infringement of trade secrets occurred under “serious circumstances”.7 As a result, in the Geely versus WM Motor case, the SPC considered the issue of punitive damages by separating WM Motor’s infringement of Geely’s technological secrets occurring before the Anti-Unfair Competition Law 2019 came into effect in April 2019 from similar infringement occurring after April 2019.

Regarding WM Motor’s infringement occurring from September 2018 to April 2019, the SPC determined that the compensation for Geely’s economic losses during this period should include compensatory damages only because the applicable, older versions of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law did not provide for any award of punitive damages.

As for WM Motor’s infringement occurring after April 2019, i.e., from May 2019 to the first quarter of 2022, the SPC stated that the compensation for Geely’s economic losses should include both compensatory damages and punitive damages. Without clear explanations, the SPC calculated the punitive damages by doubling the amount of compensatory damages during this period.

Overall, despite the limitations explained above, the SPC’s application of punitive damages is welcome as this will help deter similar large-scale infringements, resulting in better protection of IP owners’ legal rights and interests. However, although the SPC found that the circumstances under which WM Motor’s infringement occurred were intentional and egregious, it did not clearly explain why the final punitive damages were set at two times the compensatory damages, rather than five times the compensatory damages—the greatest value allowed by the Anti-Unfair Competition Law 2019—as Geely had clearly urged the SPC to consider. This uncertainty suggests that more needs to be accomplished by Chinese courts to ensure that “justice must not only be done but seen to be done”.

U.S. Experiences

“The limitations surrounding the SPC’s approach […] shows that Chinese courts may find U.S. experiences […] a useful reference when they seek to refine their approach.”

The limitations surrounding the SPC’s approach to calculating the “benefits” that WM Motor obtained as a result of its infringement shows that Chinese courts may find U.S. experiences, as outlined below, a useful reference when they seek to refine their approach.

1. Unjust Enrichment: Application and Calculation

U.S. law8 has long recognized the importance of awarding adequate damages in trade secrets misappropriation cases, both to ensure that plaintiffs are adequately compensated for their losses and that there is a sufficient deterrent to dissuade other potential infringers.

U.S. courts primarily apply a “lost profits” or “unjust enrichment” approach to calculating damages, based on which measure results in the highest award to the plaintiff. The lost profits calculation tends to be most applicable to situations where the defendant has destroyed the value of the trade secret to the plaintiff by publicly disclosing it or through some other means.9 In the unjust enrichment approach, the focus is on the benefit—whether greater sales, improved market position, savings on R&D, or other benefit—that the defendant obtained as a result of his misappropriation.

When applying the unjust enrichment approach in the United States, a judge or jury is able to calculate the benefit to the defendant with reasonable certainty10 by using one of two measures. The first measure is to determine the “sales by defendant that, absent the misappropriation, would not have been made by defendant”.11 This measure focuses on the defendant’s profits flowing from the misappropriation. In a case where a trade secret is misappropriated, unjust enrichment is typically measured by “the defendant’s profits on sales attributable to the use of the trade secret”.12

The second measure is to determine R&D costs saved by the defendant as a result of the misappropriation.13 This measure can still be appropriate in a situation where the defendant’s infringement of the plaintiff’s trade secret is discovered before the defendant can use the secret to achieve significant sales or profits.

The interplay between these two measures in practice is best illustrated by Salsbury Laboratories v. Merieux Laboratories, whose factual situation parallels the circumstances of the Geely case in certain key respects. In this case, Merieux, a French vaccine manufacturer, hired several former employees of Salsbury who had played key roles in developing Salsbury’s poultry vaccine to protect against Mycoplasma Gallisepticum (“MG”). Prior to hiring these individuals, Merieux had conducted zero work to develop an MG vaccine. Soon after these individuals arrived, however, Merieux began developing an MG vaccine and quickly made it available on the market once USDA approval was obtained.

Merieux ultimately admitted it had gained USD 52,000 in profits from its sale of the vaccine containing the knowledge inappropriately gleaned from the Salsbury employees. At both the trial court and the Court of Appeals, Merieux argued that the damages awarded to Salsbury should be limited to this amount. The Court of Appeals, in its final ruling, found that the damages for unjust enrichment should not be based on the relatively minor amount of USD 52,000 in profit, but instead should be based on the significant research, development, and marketing costs Merieux had avoided by taking advantage of Salsbury’s trade secrets. As a result, because Salsbury alleged that it had spent over USD 1 million in researching and developing its original vaccine and over USD 2 million in related marketing, the court awarded to Salsbury USD 1 million, an amount representing the R&D and marketing costs saved by Merieux due to the misappropriation. The court did not award the total amount alleged by Salsbury as damages because it found that Merieux had separately incurred its own R&D and marketing costs in bringing its vaccine to market.14

2. Approach Taken When “Unjust Enrichment” Is Unprovable

Just like the SPC facing uncertainty in the Geely versus WM Motor case, U.S. courts have encountered many situations in which neither the “lost profits” nor “unjust enrichment” approach could be applied because both “lost profits” and “unjust enrichment” were considered unprovable. For example, unjust enrichment may be difficult to prove because the infringing product containing the trade secret was never brought to market but was instead used internally by the defendant in its business.15 The difficulty may also occur when the misappropriated trade secret only constitutes a fraction of a defendant’s complex software product.16

In response to these difficulties, U.S. courts have generally adopted a principle from U.S. patent law to find that, although actual loss or unjust enrichment cannot be determined with sufficient certainty, the plaintiff is entitled, at a minimum, to a reasonable royalty from the defendant for the defendant’s use of the trade secret. To determine what a reasonable royalty would be, the court typically determines what amount a person, desiring to use another’s trade secret as a business proposition, would be willing to pay as a royalty while still being able to use the technology at a reasonable profit.17

Ultimately, an award of a reasonable royalty as damages is based on a hypothetical situation where, rather than one party obtaining the other’s proprietary information by theft or artifice, both parties had negotiated for and agreed upon a licensing fee permitting the defendant to utilize the plaintiff’s trade secret.

Concluding Remarks

As stated at the outset, in order to effectively encourage innovation, a country’s legal system must provide adequate protection for IP rights. The proper calculation of compensatory and punitive damages, particularly in trade secrets infringement cases, is a crucial part of such a system. The most sophisticated IP protection regimen in the world will have little effect if it does not provide for the recovery of compensatory and punitive damages that both reimburse the right holders for their losses and deter future infringers. The judgment issued by the SPC in this case is an important step towards achieving this goal.

- The citation of this article is: Nathan Harpainter & David Wei Zhao, Determining Damages in Trade Secret Cases: China’s Landmark Case vs. U.S. Experiences, SINOTALKS.COM®, SinoInsights™, Oct. 1, 2025, https://sinotalks.com/sinoinsights/trade-secret-damages-china-united-states.

The co-authors jointly contributed to the completion of this article, and their names are listed in alphabetical order. The original, English version of this article was edited by the co-authors and Dr. Mei Gechlik. The information and views set out in this article are the responsibility of the co-authors and do not necessarily reflect the work or views of SINOTALKS®. ↩︎

- 最高人民法院发布反垄断和反不正当竞争典型案例 (The Supreme People’s Court Publishes Anti-Monopoly and Anti-Unfair Competition Typical Cases), 《最高人民法院知识产权法庭网》(enipc.court.gov.cn), Sept. 11, 2024. For more information about “Typical Cases”, see, e.g., Dr. Mei Gechlik, Anti-Monopoly Law and Intellectual Property: More Guidance for Chinese Courts, SINOTALKS.COM®, In Brief No. 4, Jan. 26, 2022. ↩︎

- 渠丽华 (QU Lihua), 为新质生产力注入强劲司法动能 (Injecting Strong Judicial Momentum into New Quality Productive Forces), 《最高人民法院知识产权法庭网》(ipc.court.gov.cn), Feb. 28, 2025. For more information about “New Quality Productive Forces”, see, e.g., Dr. Mei Gechlik, Key Talks in 1992, Court Cases in 2024, and “New Quality Productive Forces”, SINOTALKS.COM®, In Brief No. 47, Aug. 28, 2024. ↩︎

- (2018)沪民初102号民事判决 ((2018) Hu Min Chu No. 102 Civil Judgment), rendered by the High People’s Court of Shanghai Municipality on Sept. 5, 2022. ↩︎

- (2023)最高法知民终1590号民事判决 ((2023) Zui Gao Fa Zhi Min Zhong No. 1590 Civil Judgment), rendered by the Supreme People’s Court on Apr. 25, 2024. ↩︎

- 《中华人民共和国反不正当竞争法》 (Anti-Unfair Competition Law of the People’s Republic of China), passed and issued on Sept. 2, 1993, came into effect on Dec. 1, 1993, amended and came into effect on Apr. 23, 2019. The law was further revised on June 27, 2025 and this revised version will become effective on October 15, 2025. ↩︎

- Id. Article 17. Article 22 of the 2025 version of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law is similar except that a court may choose to calculate the damages on the basis of the plaintiff’s losses or the defendant’s benefits. In other words, unlike the 2019 version of the law, the 2025 version does not require the latter approach to be applied only if it is difficult to base the calculation on the plaintiff’s losses.

For more discussion of issues related to China’s Anti-Unfair Competition Law, see, e.g., The Editorial Board of SINOTALKS®, China’s Newly Revised Law Combats Cross-Border Unfair Competition, SINOTALKS.COM®, SinoExpress™, July 16, 2025; Dr. Mei Gechlik, Data as Property in the AI Era: How China Formulates Related Rules Incrementally, SINOTALKS.COM®, In Brief No. 53, Feb. 26, 2025. ↩︎ - Id. ↩︎

- In the United States, both federal law and state law are potentially applicable to issues of trade secrets misappropriation. The law applied depends on the specific jurisdiction of the court in which an action is filed. However, the basic principles applied within different jurisdictions are broadly similar. ↩︎

- Gregory E. Upchurch, Intellectual Property Litigation Guide: Patents and Trade Secrets §20:23 (1st ed. 2025); see also University Computing Co. v. Lykes-Youngstown Corp, 504 F.2d 518, 535 (stating that “in most cases[,] the defendant has utilized the secret to his advantage with no obvious effect on the plaintiff save for the relative differences in their subsequent competitive positions.”). ↩︎

- Epic Sys. Corp. v. Tata Consultancy Servs. Ltd., 980 F.3d 1117, 1130 (7th Cir. 2020). See also The Sedona Conference, Commentary on Monetary Remedies in Trade Secret Litigation, 24 Sedona Conf. J. 349 (2023). ↩︎

- The Sedona Conference, supra note 10, at 385 (explaining in footnote numbered 54: “These unjust enrichment damages may include both diverted sales and nondiverted sales. Diverted sales are sales by defendant that would have instead been made by plaintiff but for the misappropriation. To the extent these sales are also included in a plaintiff’s lost profits claim, care should be taken to avoid double-counting. Nondiverted sales are sales by defendant that, absent the misappropriation, would not have been made by plaintiff. These also represent unjust enrichment sales.” ↩︎

- Litton Systems, Inc. v. Ssangyong Cement Indus. Co., Ltd., 107 F.3d 30 (Fed. Cir. 1997). ↩︎

- PPG Industries v. Jiangsu Tie Mao Glass Co., 47 F.4th 156 (3d Cir. 2022). ↩︎

- Salsbury Laboratories, Inc. v. Merieux Laboratories, Inc., 908 F.2d 706, 714 (11th Cir. 1990). ↩︎

- Unilogic v. Burroughs, 10 Cal.App.4th 612, 626-630 (6th Dist. Ct. App. 1992). ↩︎

- Vermont Microsystems v. Autodesk, 138 F.3d 449 (2d. Cir. 1998). ↩︎

- Id. The court applied the test of a reasonable royalty in patent cases to the trade secrets context. ↩︎