China’s Policy for Central Asia:

Lessons from Southeast Asia & More†

Table of Contents

Estimated Reading Time

- 4.9 min

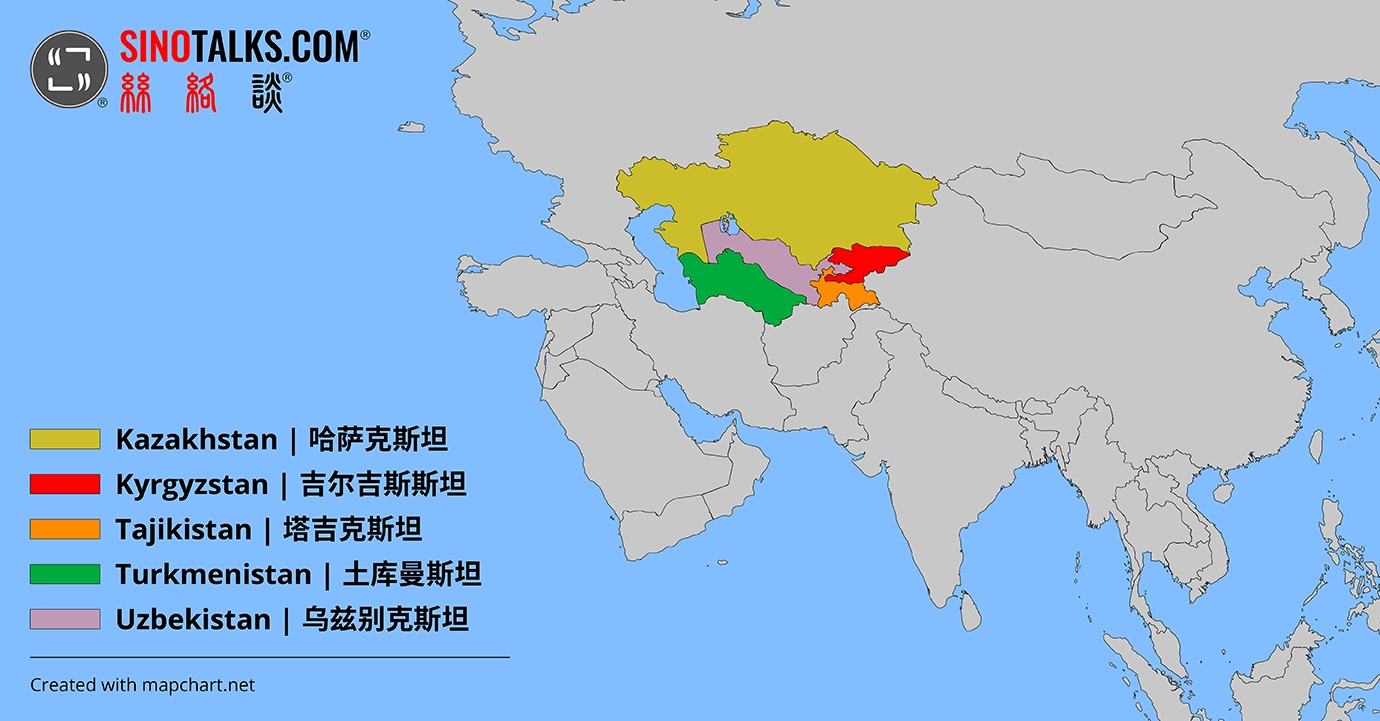

The recent establishment of the Secretariat for the China-Central Asia Mechanism represents a key step taken by China and five Central Asian nations, namely, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, to “comprehensively promote [their] cooperation”—a goal stated in the Xi’an Declaration signed by these countries during a summit held last May in Xi’an, the eastern terminus of the ancient Silk Road.

In a congratulatory letter, Chinese Foreign Minister WANG Yi expressed the country’s wish to, inter alia, “bring more benefits to the people of [China and the five Central Asian nations]”. This wish is especially welcome amidst the world’s growing concerns that poverty and social marginalization might have contributed to the rise of terrorist activities in Central Asia. How can China turn this wish into reality? A recent survey showing Southeast Asians’ unprecedented level of support for China provides some useful lessons for reference.

The Survey in Southeast Asia

In early April, the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore released its report titled The State of Southeast Asia 2024 Survey, which illuminates “the prevailing attitudes among those in a position to inform or influence policy on regional issues”.

A total of 1,994 respondents from ten member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (“ASEAN”)—Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam—participated in the survey. Most respondents are affiliated with the private sector (33.7%), the government (24.5%), or “academia, think-tanks, or research institutions” (23.6%). Other respondents work with “civil society, organizations, or media” or “regional or international organizations”.

“When asked which country they would choose if ASEAN was forced to align itself with China or the United States, 50.5% of the 1,994 respondents chose China, […].”

When asked which country they would choose if ASEAN was forced to align itself with China or the United States, 50.5% of the 1,994 respondents chose China, with the remaining 49.5% opting for the United States. In a similar survey conducted in 2023, the corresponding percentages were 38.9% and 61.1%, respectively.

The preference for China is most evident among respondents from Brunei (70.1% choosing China), Indonesia (73.2%), Laos (70.6%), Malaysia (75.1%), and Thailand (52.2%). The survey team attributes China’s popularity among these respondents to their countries’ ability to benefit from the Belt and Road Initiative (“BRI”) as well as “robust trade and investment relations” with China.

With the majority of respondents from the remaining five ASEAN countries noting their preference for ASEAN to align with the United States—namely, Cambodia (55.0%), Myanmar (57.7%), the Philippines (83.3%), Singapore (61.5%), and Vietnam (79.0%)—the fact that China received, for the first time since such survey was conducted in 2020, an overall rating higher than the United States suggests that China’s use of the BRI and trade/investment relations to bring benefits to people in the ASEAN region has been quite effective.

Same Approach in Central Asia?

This success in Southeast Asia will likely bolster China’s confidence in using the same approach, i.e., the BRI and trade/investment relations, to “bring more benefits to the people” of the five nations of Central Asia. In fact, China has been using this approach in these nations. For example, in 2023, trade between China and the five Central Asian nations rose by 27.2% year-on-year to reach USD 89 billion.

With respect to the BRI and investment relations, Chinese media have published a series of reports covering related activities in these five Central Asian nations. Overall, Kazakhstan has shown remarkable progress, to the extent that the country has set the ambitious goal of doubling its national economy to USD 450 billion by 2029. In Turkmenistan, China has focused on helping the country to expand its oil and gas production in western Turkmenistan, taking advantage of its proximity to the Caspian Sea.

China’s use of the BRI and trade/investment relations to “bring more benefits to the people” of Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan seems to have produced results. Both countries have witnessed economic growth and their GDP per capita have respectively reached USD 12,968 (ranked 69th in the world) and USD 12,934 (ranked 70th), according to the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook Database.

Unlike Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan, which border the Caspian Sea, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan are landlocked. This geographical disadvantage, together with the three countries’ underdevelopment (with GDP per capita being USD 1,830, USD 1,180, and USD 2,509, respectively), seems to have limited China’s options. Most activities in these three countries with Chinese involvement are related to the construction of roads and railways (e.g., the China-Kyrgyzstan–Uzbekistan transport corridor and the Vahdat-Yavan railway tunnel connecting China with Tajikistan) to increase their connectivity.

“[…] it is unwise to leave these 53 million people […] to wait and feel left out as they witness the rapid development taking place in their neighboring countries.”

It takes time for these infrastructure projects to complete construction, let alone produce economic results to bring benefits to the people in Kyrgyzstan (7 million), Tajikistan (10 million), and Uzbekistan (36 million). However, it is unwise to leave these 53 million people—who account for two-thirds of the total population of the five nations of Central Asia—to wait and feel left out as they witness the rapid development taking place in their neighboring countries. China needs to take creative measures, beyond those used in Southeast Asia, to help these people taste the fruits of success in the region, or they could be misguided by destructive forces that have the potential to undermine the region’s stability and budding prosperity.

- The citation of this article is: The Editorial Board of SINOTALKS®, China’s Policy for Central Asia: Lessons from Southeast Asia & More, SINOTALKS.COM®, SinoExpress™, Apr. 10, 2024, https://sinotalks.com/sinoexpress/202404-english-central-asia-policy. ↩︎

Related Articles

Contact Us

Get Involved

Sponsor/Donate | 赞助/捐赠

Become SINOTALKS® Partners | 成为丝络谈™合作伙伴

Services